Efficiency For All

A review of provincial low-income energy efficiency programs with lessons for federal policyAbhi Kantamneni

Research Associate, Efficiency Canada

Brendan Haley

Policy Director, Efficiency Canada

March 31, 2022

Blogs | Energy Poverty | News

- Energy poverty needs to be prioritized at the national level if the transition to net-zero emissions is to be fair and just.

- The federal government can play a leadership role by expanding the scale and scope of low-income energy efficiency.

- A productive and appropriate role for the federal government is augmenting and leveraging the delivery capacity of existing programs towards reducing energy poverty and achieving net-zero emissions.

Energy poverty needs to be prioritized at the national level if the transition to net-zero emissions is to be fair and just, and energy efficiency should benefit all Canadians. Our recent research report ‘Efficiency For All’ outlines the most appropriate and productive role the federal government can play in ensuring energy efficiency helps those most in need. Read the report here and scroll down to the end of this post to access the provincial low-income program database.

Why low-income energy efficiency matters:

Low-income households in Canada are more vulnerable to energy poverty – characterized as a condition where a household faces significant barriers meeting essential home energy needs such as heating and cooling, and/or faces challenges paying for their energy costs. Energy poverty is caused by three main issues: low incomes, high energy prices, and/or energy-inefficient homes. Even though lower-income households experiencing energy poverty can benefit the most from energy efficiency upgrades, they are unlikely to install such upgrades without well-designed and relevant policy support. Low-income households cannot afford up-front costs for energy efficiency measures, or assume more debt burden to finance upgrades. Tailored programs are needed to reach these households. In Canada, the need for a specific low-income program approach is recognized by utilities and provincial governments that provide energy efficiency services. However, the federal government has yet to provide specific support to improve low-income energy efficiency. For Canada to meet net-zero transition goals while leaving no one behind, expanding the scale and scope of low-income energy efficiency is an urgent national policy priority. To do this, the report reviews existing low-income energy efficiency programs at the provincial and territorial levels, discusses general strengths of these programs as well as the common gaps, and identifies strategies the federal government can follow that complements existing programs in the market while achieving specific policy objectives of reducing energy poverty and meeting net-zero goals.Key Features of Existing Programs:

- Programs vary in terms of common delivery strategies, energy-saving measures, and target markets.

- Self-install programs supply easy-to-install energy saving kits, sent directly to qualifying renter or homeowner households.

- Direct-install programs provide professionally installed minor or major upgrade measures at no cost to the participating household based on an initial home energy assessment.

- Custom measures programs for multi-unit buildings offer energy savings measures ranging from technical assistance to in-suite measures customized for the multi-unit buildings’ energy needs and built environment.

- Product rebate programs augment existing product rebates to provide equipment at no cost or at a significantly reduced cost for income-qualified households.

- Supplemental programs, typically found in northern Canada, focus on enabling homeowners to make health, safety, and mobility upgrades to their existing homes. Improving energy efficiency is one component of such programs.

- Programs with shallow measures reach more households but robust funding can achieve higher participation even for programs providing more comprehensive major retrofit upgrades .

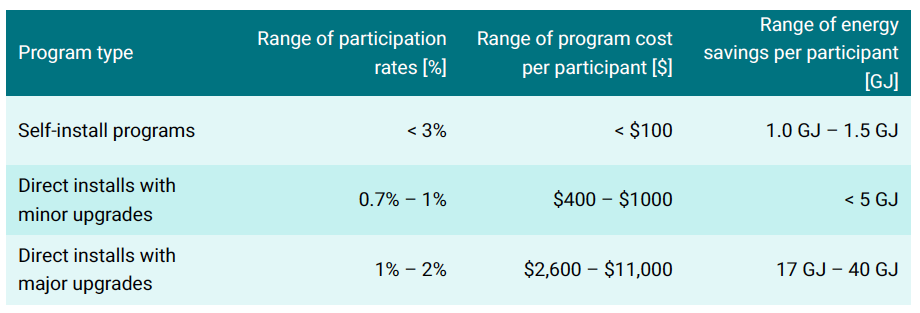

Table 1: High level findings by program type

Key Strengths of Existing Programs:

Existing programs have two general strengths for delivering energy reduction measures to low-income households:- Several low-income programs successfully engage a relatively large number of low-income Canadians in energy efficiency. We estimate that annually around 55,000 Canadian households participate in a provincial low-income energy efficiency program.

- This reach is facilitated by a deep institutional knowledge program that administrators have accrued over many years of program design, outreach, and delivery. Each program’s delivery efforts are geared specifically to the provincial context they operate, and no two programs are alike.

- Few programs in Canada specifically target energy poor households experiencing disproportionate energy cost burdens, households living in least efficient homes, and/or households facing additional challenges such as language barriers or issues navigating systems of support.

- The depth of investments and savings achieved per household needs to increase substantially above current program levels to be consistent with net-zero emissions and climate change goals.

- Switching to zero-carbon ready highly efficient heating systems (e.g., electric or hybrid heat pumps) is not a widespread standard feature in any program, even when such switching could significantly reduce overall bills when coordinated with other energy efficiency measures.

- Existing programs do not have a mandate to address remedial health and safety issues in homes such as mold removal or structural upgrades, even if such measures may enable future energy efficiency upgrades.

Federal role in low-income energy efficiency:

The federal government has the responsibility to meet international climate commitments and national climate goals. The national level is also most capable of considering holistic benefits associated with energy poverty reduction, such as adequate and appropriate housing that meets people’s needs and supports their physical health and mental well-being. With these objectives in mind, we present four policy design considerations for a federal low-income energy efficiency strategy that works best with existing provincial level programs:- Focus on long-term results: Federal policy should set targets and prioritize results that will achieve net-zero emissions, and energy poverty reductions, while allowing provincial and territorial programs to fit their individual contexts.

- Develop and enhance existing programs: The federal government’s capabilities should be focused on acting as a project manager and enabler that increases ambition and monitors the success of the transition to net-zero emissions in an equitable manner, rather than tying up federal resources with program implementation..

- Secure stable long-term funding: The federal government should make a multi-year funding commitment to avoid boom-bust dynamics that have previously disrupted energy efficiency programs and broken participant trust. A federal initiative that encourages and supports provincial specific program designs will institutionalize these programs within provincial policy systems, and thus provide an added layer of political resilience.

- Create supportive systems: The federal government is uniquely positioned to creating supportive systems and providing enabling tools such as detailed data on energy poverty; enhancing workforce capabilities and welcoming new people into energy efficiency careers to improve program reach and trust among hard-to-reach communities; and developing net-zero standards by building typology and region to guide the goals of each low-income retrofit.