A national energy poverty strategy for Canada?

What we can learn from national initiatives in other jurisdictions

Abhi Kantamneni

Brendan Haley

December 13, 2021

Blogs | Low-Income Energy Efficiency | News

- Canada needs a national strategy on reducing energy poverty.

- The federal government can play a leadership role by expanding the scale and scope of low-income energy efficiency.

- Other jurisdictions show it is possible to use targeted energy efficiency retrofits to support low-income households with high energy costs and GHG emissions, even in a complicated federation like Canada.

All signs point to rising energy costs and extreme weather this winter. These potential events are most concerning for lower income households who often have to make tough choices between heating, eating and other household essentials. Using standard measures¹ of what is called “energy poverty”, one in five Canadian households face unreasonable energy cost burdens.

Yet, no federal program is currently accessible to low-income homeowners and market renters to help them through this winter, the extreme heat we experienced in summer, or to prepare for a net-zero emissions economy. Almost every province in Canada has some form of low-income energy efficiency and energy assistance program, yet funding levels are far below what is required to meet net-zero emission objectives and these programs face policy constraints that prevent them from achieving deeper energy savings.

There is an urgent need for the federal government to take a leadership position in expanding the scale and scope of low-income energy efficiency. Luckily there are lessons that can be learned from other national or federal initiatives. This blog summarizes some of those lessons for us here in Canada.

Lesson 1:

Make targeting least efficient and lowest income households a core part of energy poverty reduction strategy

‘Reducing energy poverty’ formally became a legislated duty of the UK government with the passage of Warm Homes and Energy Conservation Act of 2000 (WHECA). The subsequent UK national fuel poverty reduction strategy first developed in 2001 laid out responsibilities for the UK Government and set non-binding aspirational goals of ‘ensuring, as far as reasonably practicable, no person lived in fuel poverty by 2016’. Fuel poverty was characterized as the challenge experienced by “households of a lower income, living in a home which cannot be kept warm at a reasonable cost”. ‘Reasonable cost’ was determined to be 10% of household income spent on energy in the home, which at that time represented twice the national median household expenditure (5% of income) on home fuel costs in the UK.²

In an effort to better “link fuel poverty, social justice and climate agenda” and to “ensure fuel poverty remains high on national policy agenda”, the UK Government updated its fuel poverty strategy in 2015, binding future governments to improving energy efficiency as the explicit strategy for reducing energy poverty. This ‘improve efficiency’ strategy was further enshrined in statutory targets: ensuring as many fuel poor as reasonably possible achieve a minimum home energy efficiency rating³ better than or equal to the top 20% of the most efficient houses in the country. By focusing on improving energy efficiency for fuel poor households, the UK Government sought to “make a real, lasting difference to household bills regardless of future energy prices”.

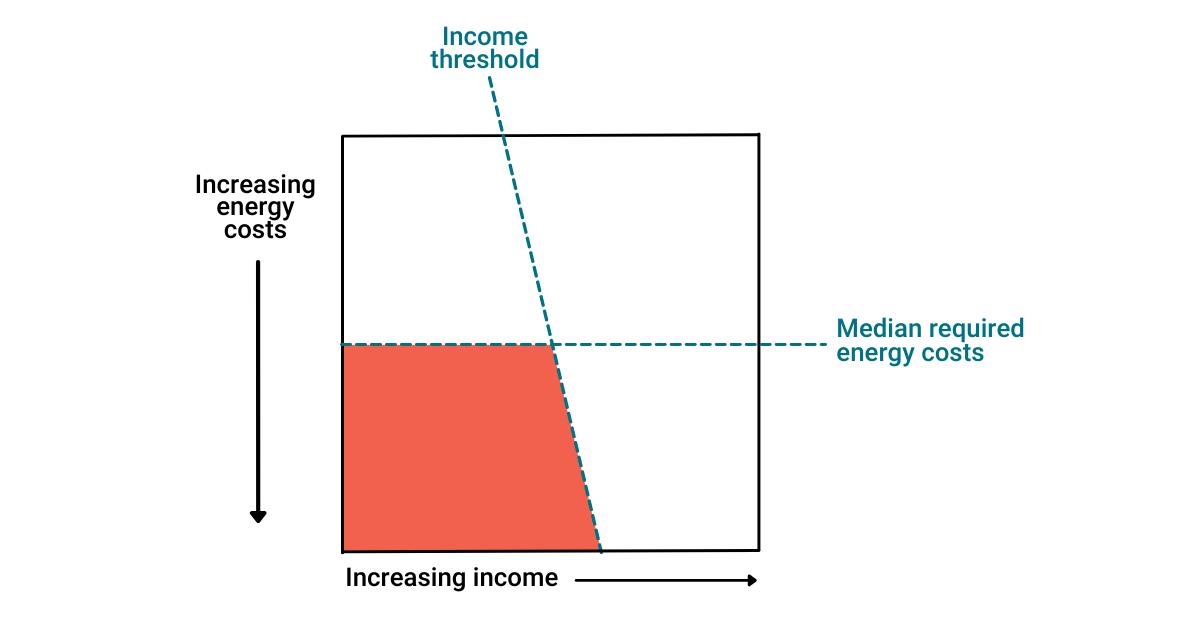

The 2015 fuel poverty strategy also adopted a new indicator – Low Income High Cost (LIHC) – as an official measure of energy poverty. The LIHC indicator takes into account the fuel poverty gap – how much more energy an energy poor household needs to meet its home energy needs. This new measure identifies households that are pushed into poverty as a result of high fuel costs and low-incomes, helping policymakers prioritize and target energy efficiency upgrades towards households that require the most significant reductions in fuel bills to move out of energy poverty.

Figure 1: A representation of Low Income High Cost Indicator – which identifies households that are pushed into poverty as a result of high fuel costs and low-incomes (Adapted from Climate Just)

A more recent update to UK energy poverty strategy in 2021 introduced a new measure of energy poverty – Low Income Low Energy Efficiency (LILEE) – which identifies energy poor households living in the most inefficient homes in the country. The LILEE measure helps the UK Government target policies towards upgrading homes that are most energy inefficient and track progress towards the statutory goals of improving energy efficiency for fuel poor households, and help. Additionally, the 2021 fuel poverty strategy also commits the Government to aligning energy poverty objectives with other strategic national priorities like meeting climate targets, improving housing stock, protecting the health of vulnerable communities and ensuring fuel poor don’t get left behind in energy transitions.

Lesson for Canada: There are several strategies to reduce energy poverty such as emergency assistance and rate/bill design from utilities. The federal government can play a strong role in reducing energy poverty by contributing to the long-term solution of improving energy efficiency as a core part of the policy mix. To do this, they must target deep retrofits for the most inefficient and lowest income Canadian homes, which also contributes to achieving other national priorities like reducing GHG emissions and ensuring vulnerable communities are not left behind in the transition to a net-zero future.

Lesson 2:

Dedicate low-income funding and design to mobilize more provincial action

The European Union is launching a Social Climate Fund to support vulnerable Europeans during the transition to reducing net continent-wide emissions by 55% by 2030.The Social Climate Fund supports measures and investments in increased energy efficiency of buildings, decarbonisation of heating and cooling of buildings, including the integration of energy from renewable sources, and improving access to low-emission transportation.

Financed by the EU budget, the Fund dedicates a minimum of 25% of revenues (€72.2 billion for the period 2025-2032) from carbon emissions trading for building and transportation fuels into supporting a ‘socially fair transition’. EU member states are required to match the funding allocation and implement measures and investments to principally benefit vulnerable households, micro-enterprises or transport users. By mobilizing matching funding from EU member states, the EU commission is able to mobilize at least €144.4 billion for a socially fair transition.

Lesson for Canada: Dedicate specific investments and set performance targets for low-income households in federal government spending on energy retrofits and climate action. Design federal climate funding to mobilize greater commitments from provinces towards investments in reducing energy poverty and improving energy efficiency for vulnerable households.

Lesson 3:

Leverage existing delivery capabilities & complement them to achieve greater savings

The US Department of Energy’s Weatherization Assistance Program (WAP) is widely regarded as ‘Longest Running and Perhaps Most Successful U.S. Energy Efficiency Program’ for its consistent investments in improving the energy performance of dwellings in need and helping low-income families reduce energy bills by making their homes more energy efficient. In the 45 years since inception, WAP has delivered no-cost energy-savings upgrades to approximately 7 million homes, cutting more than 2 million metric tons of CO2 every year and supporting more 8,500 jobs in communities across the US.

Although WAP is funded through appropriations from federal congressional budgets, weatherization assistance services are administered independently by each of the 50 states, federal territories and Indigenous communities that receive the funding. The US Department of Energy provides core program funding directly to the states and territories based on an allocation formula that accounts for severity of local climate, number of low-income households, and residential energy cost burdens experienced by such households. Grantee states, territories and Indigenous governments then engage a large network of over 700 local organizations, community action agencies and service agents to deliver weatherization services at no-cost to eligible low-income households in every county in the United States of America.

WAP offers grantee states and territories flexibility in low-income energy assistance program design. Grantees leverage WAP funding to supplement ongoing energy assistance programs in line with their own local circumstances and policy priorities. For instance, states like Colorado are using WAP funding to prioritize GHG reductions alongside weatherization by deploying rooftop solar PV for low-income households. Other states like Illinois are pursuing deeper energy savings by expanding the weatherization services provided to a maximum of $16,000 per eligible household, above and beyond the $7,200 average expenditure limit per household set by WAP (for the program year 2018). Meanwhile, states like New Mexico are offering additional measures for improving health and safety (eg: installing smoke and CO detectors), and performing incidental home repairs necessary to carry out weatherization activities in low-income households.

WAP also helps unlock additional investments from states, utilities and municipalities to support low-income energy efficiency programs. Recent analysis (from 2019) shows that grantee states and territories supplemented the $278 million in WAP funding by contributing an additional $848 million (or $3.03 for every WAP dollar) in state, utility, private and other federal funding towards no-cost weatherization assistance programs and home energy upgrades for low-income households.

The recently announced White House Build Back Better (BBB) Framework proposes an additional $3.5 billion investment into WAP energy efficiency measures in low-income households.. The BBB Framework also aims to leverage the delivery capabilities of the WAP network to achieve deeper savings through larger investments in energy savings and emission reduction measures per participating household. To this end, the BBB will increase the maximum limit of average WAP costs per participating household to $12,000 from the current threshold of $6,500, and double the maximum limit of average costs per household of renewable energy upgrades to $6000 from the current $3000. In addition, the BBB will further invest an additional $0.85 Billion into awarding financial assistance to make non-energy improvements in low-income households so they are prepared for energy efficiency upgrades.

Lesson for Canada: A national weatherization assistance program with dedicated federal funding for the next few decades that leverages the delivery capabilities of provincial low-income energy efficiency programs and re-orients them towards reducing energy poverty, cutting emissions and achieving deeper energy savings for all Canadians.

A National Energy Poverty Strategy for Canada

Canada needs a national strategy on reducing energy poverty.

Drawing on insights from other national low-income energy efficiency policies and programs, an effective national energy poverty strategy would:

- Set statutory energy poverty reduction targets to ensure energy poverty remains high on the policy agenda for current and future federal governments.

- Pursue energy efficiency as the key pathway to align reducing energy poverty with cutting emissions and achieving other national policy goals.

- Identify, target and prioritize deep retrofits for the most inefficient and lowest income Canadian homes.

- Set specific investment and performance targets for low-income households in federal government spending on energy retrofits and climate action.

- Design federal climate funding to mobilize greater commitments from provinces towards investments in reducing energy poverty and improving energy efficiency for vulnerable households.

- Launch a national weatherization program with dedicated federal funding for multiple decades. Such a program would leverage the delivery capabilities of provincial/territorial low-income energy efficiency programs and re-orient them towards reducing energy poverty, cutting emissions and achieving deeper energy savings for all Canadians.

Other jurisdictions show that it is possible to support low-income Canadians with high energy costs and GHG emissions in a complicated federation like Canada. Efficiency Canada is currently doing some research that takes stock of existing provincial low-income programs that will provide more ideas on how the federal government can plug gaps and effectively expand low-income efficiency. Stay tuned.

Stay up to date on our low income energy efficiency work! Join our mailing list.

Footnotes

¹A detailed breakdown of different energy poverty indicators used by governments around the world is a topic for a future blog.

²In Canada, the median Canadian household spends 3% of household income on home energy needs. Using a similar ‘reasonable cost threshold’ measure, Canadian households spending more than twice the national median (i.e. 6%) of household income on home energy are considered to be in ‘energy poverty.’ This works out to about 3 million homes or about one in five Canadian households that experience energy poverty.

³Tracking home energy ratings is made possible by the fact that the UK Government requires every home bought, rented or sold to have an Energy Performance Certificate (EPC). An EPC rates a home on an energy efficiency rating from A (most efficient) to G (least efficient) and is valid for 10 years. To learn more about how building labelling can lay the foundation for improving building performance in Canada, check out this blog by Efficiency Canada’s Efficient Buildings Lead Kevin Lockhart: